Mina is an eleven-year-old girl who is the first child in her family to be on the cusp of graduating from primary school. She is the third of six children of subsistence farmers who have been pushed below the poverty line by COVID.

Abdul is an eleven-year-old boy who is the first child in his family to be on the cusp of graduating from primary school. He is the last of six children of daily wage construction workers who have been pushed below the poverty line by COVID.

The new report published by UNESCO: ‘Leave no child behind: Global report on boys’ disengagement from education’ makes the case that we need to focus more attention on Abdul because he is at risk of not continuing to secondary school and the world has not paid enough attention to this threat to his right to education.

“What about men?”, “what about boys?” are common responses to work for girls’ and women’s empowerment. In most cases, these responses do not come with an understanding of the different situations of women and men, girls and boys where girls and women usually have less resources, opportunities and are more vulnerable to losing their rights. This report does not fall into that category. Rather, it is carefully positioned not to be a comparative study of boys versus girls (Box 1). Nevertheless, an implicit take-away of the report is that investment and focus of education actors must focus on boys.

Through this blog we argue that it is important to contextualize enrolment, learning and completion data within the larger situation of girls and boys without which some of the findings in the report may lead to incomplete or even incorrect conclusions. We find that girls’ education remains a compelling entry point to tackle deep-seated inequalities in the education system, particularly in countries furthest from achieving SDG4 and especially as a response to COVID school closures. Finally, we propose that gender equality in and through education is a more productive banner than boys’ education or indeed, girls’ education.

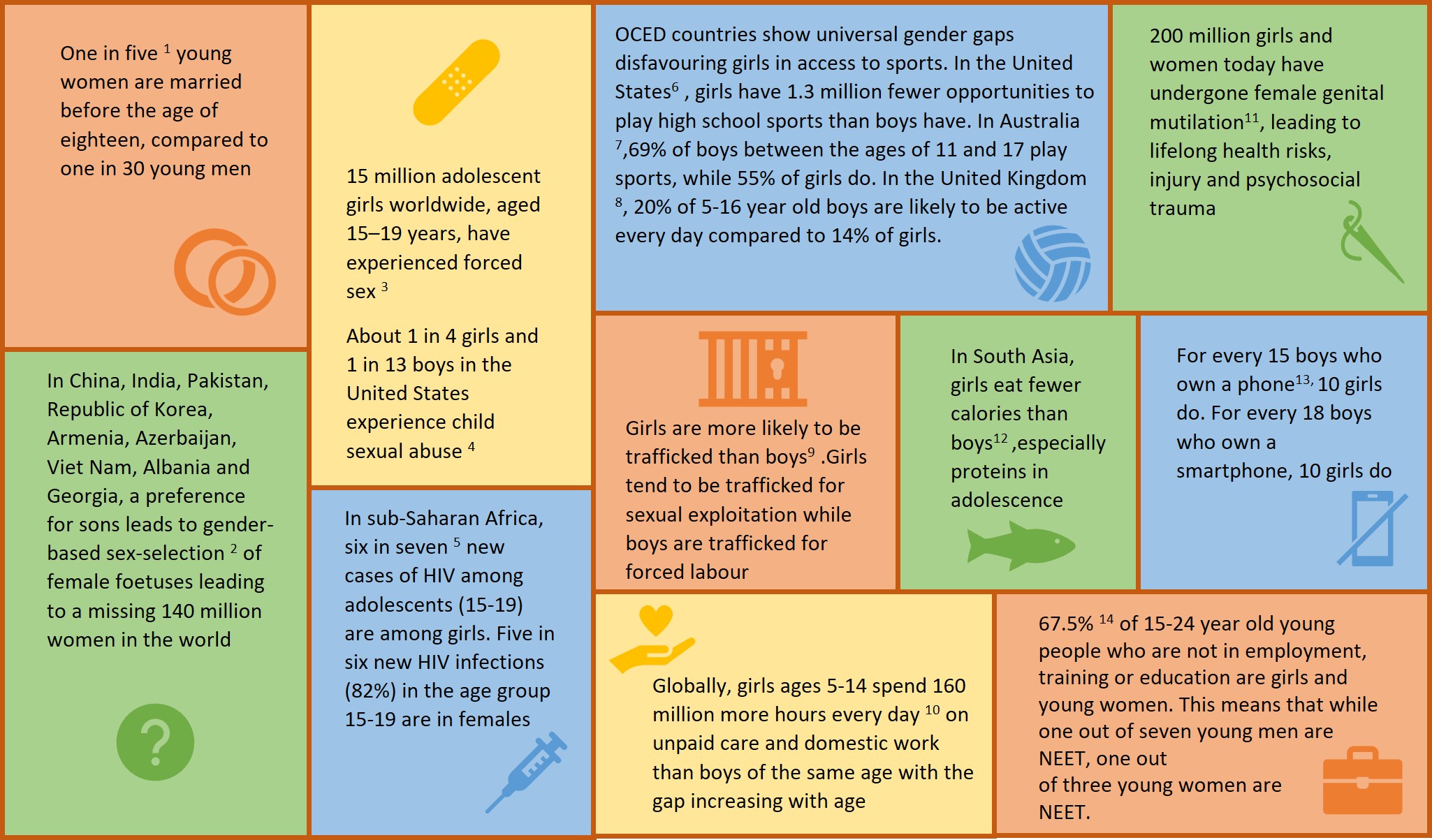

1. Girls face greater threats to their rights and have fewer resources and opportunities.

Data on parity gaps in enrolment, learning and completion are most useful when situated in the context of gender advantage and disadvantage more broadly. Consider the following statistics:

Reference links: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14

These statistics showcase several aspects in which girls are systemically disadvantaged because of their gender which directly impacts their opportunities and resources to fully, and equally participate in education. Whilst this blog is focusing on boys and girls, it is important to highlight a severe lack of data on LGBTQI children, which requires urgent attention.

2. Data on secondary school enrolment and learning is mixed, within and between countries.

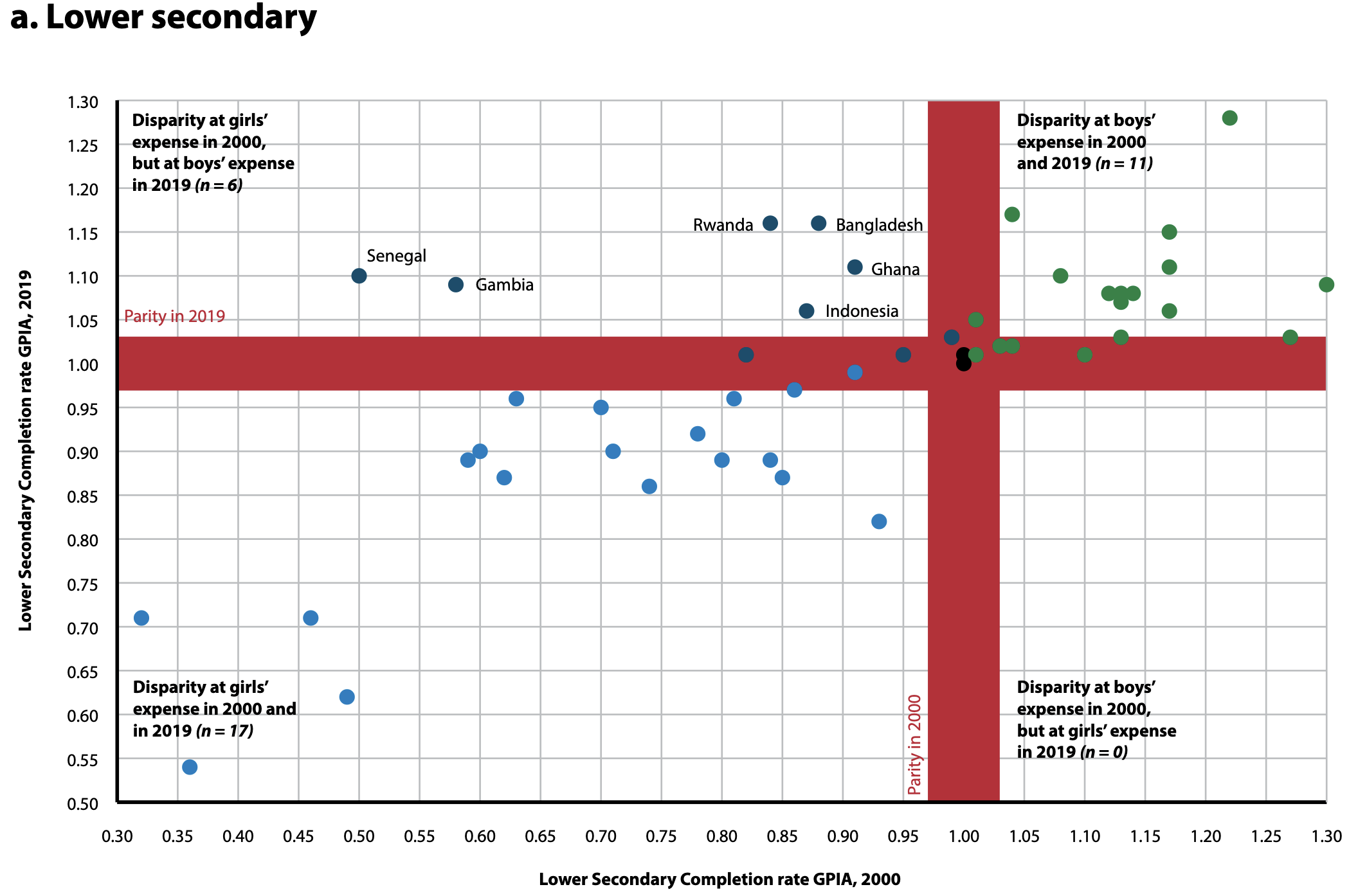

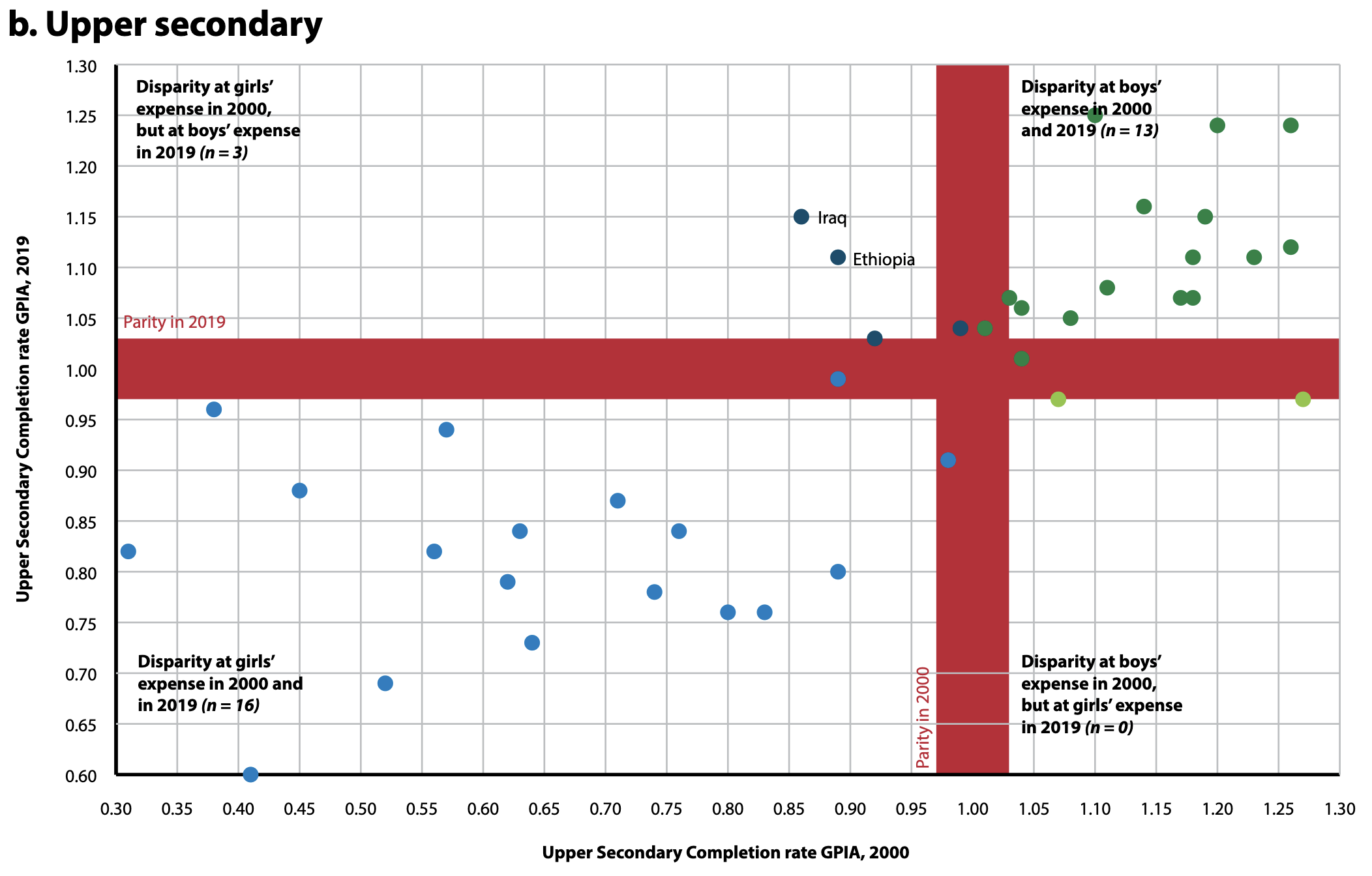

Some low- and middle-income countries are moving towards gender parity, which is good news. However, as shown in Figures 5a and 5b of the UNESCO report, girls continue to lag behind boys in terms of completion in secondary school in a number of countries. As noted by UNICEF, this is more often the case in countries in the Middle East, South Asia, and Africa, which are further behind in the SDGs. Caution is needed in interpretation in some countries where it appears that there is a reversal in the gender gap. For example, Ethiopia is identified as a country in Figure 5b where more girls are in upper secondary school than boys. This is because so few make it to this stage, whether girls or boys. According to latest data from UNESCO’s WIDE database, upper secondary graduation in Ethiopia is around 14% for girls and 12% for boys. When disaggregated by wealth, a mere 1% of boys and 2% of girls are estimated to reach this stage.

Figure 5: Gender parity index (adjusted) for completion rates at secondary level (Source: UNESCO report, Page 36)

The UNESCO report identifies that girls’ learning outcomes are better than boys’ in a number of contexts. This is often in situations where overall learning is very low so signifies the need to improve the quality of education across the board. Whether COVID-related learning losses have differed for girls and boys cannot yet be determined since we are still collecting and analyzing the data. Some national reports like ASER in Pakistan show that girls’ declining in reading Urdu declined more than boys’ even though they had been outperforming boys prior to COVID. According to The State of the Global Education Crisis: A Path to Recovery by UNESCO, UNICEF and the World Bank, learning losses for girls in South Africa were 20% and 27% higher for girls than boys in home language and English reading respectively, and a citizen-led assessment in Mexico found larger learning losses for girls than boys.

In addition, COVID-19 has brought to the fore that it is also important to go beyond assessing literacy and numeracy, for example to also understand effects of schooling on socio-emotional learning for girls and boys. This encompasses a range of skills important for student’s development both within and outside of school, and is found to have associations with children’s mental health and wellbeing. Extending an understanding of learning can be of particular importance for supporting students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Importantly, whilst some data show that the tide may be turning on gender parity, what must be made clear is that it does not mean gender equality has been achieved. Gender parity, i.e. an equal proportion of girls and boys in school and/or learning, is a clear and uncomplicated measure which appeals to policymakers and practitioners, but it does not give the full picture. It does not however mean that the more ambitious goal of gender equality, involving wider steps to end discrimination and create a truly level playing field, has been achieved.

3. Gender-based violence is likely to have greater effects on girls

Data on gender-based violence remains limited and can be difficult to measure accurately. As noted in the UNESCO report, boys in school are impacted by physical bullying and corporal punishment especially those who are or are perceived to be LGBTQI. At the same time, girls are more likely to be victims of non-consensual sex attempts in schools and this is worsened in times of conflict. Fear of sexual violence can cause girls to drop out or be pulled out of school by parents, and girls who drop out are at more risk of being married off earlier, placing them at higher risk of child marriage. In addition to losing vital education, such attacks can have particularly debilitating long-term consequences for girls, including early pregnancies, and stigma associated with sexual violence and rape. In addition, girls are affected by female genital mutilation, and being conditioned that gender violence is the norm.

4. Gender stereotyping in schools perpetuates girls’ inequality later on in life

As pointed out in Box 13 of the UNESCO report, textbooks can heavily influence the construction of gendered identities and gendered roles, often showing men in dominant commercial roles and women in subordinate, subservient roles. This affects boys’ and girls’ sense of self and sets trajectories for their later life expectations, leaving girls more likely than boys to get lower paid jobs.

Whilst some progress has been made in this area, the stereotyping of education textbooks and curriculum persists in many societies. This is partly due to women not being involved in the process of developing textbooks and curriculum, an exclusion which is connected to wider gender inequalities linked to lack of women in leadership roles and gendered job roles.

5. Child work affects girls and boys differently

One of the primary reasons identified in the UNESCO report for boys dropping out of school is the expectation placed on them to generate an income for their family, or indeed themselves, and so they may choose to work in often low paid, labour jobs. This choice can sometimes be driven by the poor quality of education, and so work is considered a preferable alternative. In some circumstances, their paid work can enable them to pay for schooling expenses where they are able to combine the two. Whilst girls may not have this societal burden placed on them, they are more likely to drop out of school because of the need to work or care for family. In some cases, they are expected to combine these activities with their education, resulting in them being absent from school. In other cases, girls’ work is often insecure, unproductive, and unsafe and puts girls at risk of sexual exploitation and sexual violence.

The UNESCO report indicates that girls are more likely to be neither in education, employment nor training [NEET], but also that high numbers of boys are in this situation. According to a global SDG technical brief by ILO, “67.5 percent of 15-24 year old young people who are NEET are girls and women. Whereas one in seven (14.0 per cent of) young men are NEET for young women the figure is closer to one in three (31.2 per cent)”. This is because of the wider systemic multi-layered gender barriers that girls and women face. Another ILO study on youth employment shows that in general, women have more difficulties finding employment than men, and even when they have higher education levels, women face labour market discrimination which favours hiring and promoting men over women.

Impressing this point, a study assessing the effect of COVID-19 on adolescents showed that, whilst the pressure for adolescent boys to get paid work was higher, girls faced marked disadvantages in accessing remote learning due to the digital gender gap, and girls were plagued with increased burdens of unpaid domestic and care work. Indeed a recent UNICEF report suggests that during the pandemic, globally, women and girls carried out on average three times the amount of unpaid care and domestic work of men and boys.

The bottom line: it’s not girls versus boys, it’s ALL children against gender inequality

Our vital work on gender equality in education should not be a battle ground in which ‘boys vs girls’ are the two sides. Instead, we should all march together under the banner of gender equality in and through education, a banner which will rightfully help boys to question and reject harmful, narrow and violent norms of masculinity just as it will help girls develop and consolidate their agency so they can take up their rightful place as equal citizens. Gender equality in and through education means many things including gender-responsive pedagogy and curricula, parity at all levels of teaching and administrative staff, nurturing, supportive schools, intergenerational conversations and learning that center social justice, especially climate action. Fortunately, we already have many such programmes in place, several of which are identified in the UNESCO report.

Raising the floor for the most disadvantaged has been proven to be a valuable entry point for all children. This is well demonstrated by CAMFED’s multidimensional model, which uses girls’ education as an entry point but supports all of those living in poor, rural communities within the countries in Africa in which they work.

Mina and Abdul, the children we started this piece with, need every bit of help they can get. The devastating truth is that it is likely that neither of them will start secondary school. The devastating truth is also that Mina is vulnerable to child marriage, trafficking, FGM and every day sexual violence. The devastating truth is also that the patriarchy that leads to these risks are also probably the reason Abdul has five older sisters in wait for a son and that if his family does manage to save money for education, it will go to him and not his sisters. Both Mina and Abdul need a world in which there is no gender-based discrimination and they can freely access an equitable and inclusive quality education to grow into equal and productive citizens of their communities and our world.