In 2021, with less than 10 years until the Sustainable Development Goal 4 target deadline of 2030, the G7 heads of state set and endorsed a pair of global objectives on girls’ education to be achieved by 2026 in low- and lower-middle-income countries:

- 40 million more girls in school; and

- 20 million more girls reading by age 10 or the end of primary school.

The emphasis was on the most marginalized and vulnerable girls, as a result of poverty, disability, conflict, displacement and natural disasters, who are being left furthest behind. These were intended to be stepping stones to the 2030 targets of universal primary and secondary completion and minimum learning proficiency for all.

A baseline report, released today by the GEM Report, the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS), the United Nations Girl’ Education Initiative (UNGEI) and the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), presents evidence from national and global actors on low- and lower-middle-income countries’ starting points relative to the two global objectives just before the pandemic struck, and the prospects of achieving them. The report accompanies the efforts of the G7 Accountability Working Group to monitor those objectives.

Objective 1: Ensuring that 40 million more girls are in school in the next five years is hard but achievable

In order to achieve the first objective, the number of out-of-school 6- to 17-year-old girls would have to fall from 101 million to 61 million girls or by 40%. The global objective is equivalent to a decline in the out-of-school rate from 22% to 13%. This is more ambitious than the national SDG 4 targets countries have set: if they achieve these targets, the out-of-school rate would fall to 15% or by 30 million.

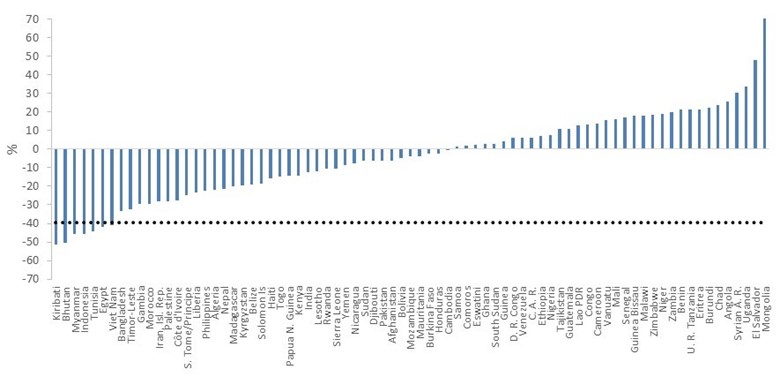

Out of 77 low- and lower-middle-income countries with data, few counties achieve such a pace of progress in five years. Between 2015 and 2020, the number of out-of-school girls fell by at least 40% in just 7 countries Bhutan, Egypt, Indonesia, Kiribati, Myanmar, Tunisia and Viet Nam. However, no low-income country achieved such progress.

Proportional change in the number of out-of-school girls, low- and lower-middle-income countries, 2015–20

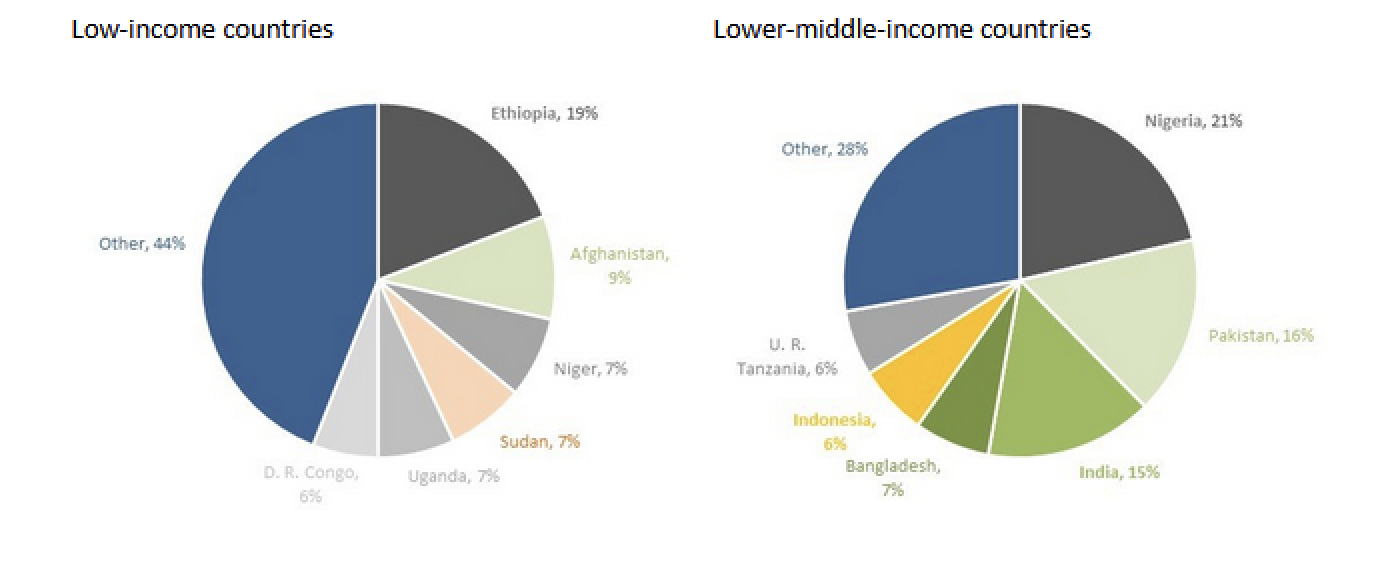

As of 2020, six low-income countries with the highest number of out-of-school girls accounted for 56% of the total. Ethiopia’s 6.2 million girls out of school account for 19%, followed by Afghanistan, Niger, Sudan, Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The short-term prospects are challenging for three of them, with Afghanistan the most extreme case following the ban on girls attending secondary school announced in March 2022, the consequences of the civil war in Ethiopia, and major concerns about COVID-19’s aftermath in Uganda, the low-income country with the most prolonged school closures.

Six lower-middle-income countries with the highest number of out-of-school girls accounted for 72% of the total. Nigeria’s 12.2 million girls out of school account for 21% of the total, followed by Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, Indonesia and the United Republic of Tanzania.

The G7 outlined how they would specifically help achieve this objective in the Declaration on girls’ education: recovering from COVID-19 and unlocking Agenda 2030.

Share of countries with largest number of out-of-school girls, by country income group, 2020

Girls’ exclusion remains high in countries such as Benin, Cameroon, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Mali and Togo in sub-Saharan Africa and, especially, Afghanistan and Pakistan in South Asia. They should be a focus of global efforts to achieve gender parity.

Young women of upper secondary school age are more likely to be out of school in most lower-middle- and in practically all low-income countries. In some countries, including Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mozambique and Sudan, rural and poor girls are at a particular disadvantage.

Objective 2: Ensuring that 20 million more girls will be able to read with understanding in the next five years will be harder

It is more difficult to assess the likelihood of achieving this objective because data on learning levels are only available for 29 of 82 low- and lower-middle-income countries. Data on trends are even more scarce.

Using the best available estimates, 31%, or 61 million girls, achieved the minimum proficiency level in reading at the end of primary school in 2020. If the number of girls achieving that level increases to 81 million within a period of five years, the percentage of girls would need to increase to 37%. This is equivalent to an annual increase of 1.2 percentage points. This is ambitious in the sense that more than double the rate currently observed. But it is less ambitious than what countries have set as national SDG 4 benchmarks.

In 27 out of 29 countries for which there is data on learning, girls are a few percentage points ahead of boys in being able to read a simple text by the end of primary school. But the most urgent takeaway is that only a minority of in-school children meet this criterion. As national and global experts point out in the report, this does not take into account the children who never enrolled, never attended or dropped out of school. They note, additionally, that the COVID-19 pandemic both increased this number and harmed the learning levels of those in-school.

The two global objectives are but a part of the struggle for gender equality in and through education

These two global objectives are only part of the wider effort to achieve gender equality. Even in countries where there are more out-of-school boys than there are out-of-school girls, girls and women still have lower access to formal paid work, fewer assets, less access to credit, higher risks of gender-based violence and discrimination, and are more vulnerable to losing their rights.

These two global objectives are only part of the wider effort to achieve gender equality. Even in countries where there are more out-of-school boys than there are out-of-school girls, girls and women still have lower access to formal paid work, fewer assets, less access to credit, higher risks of gender-based violence and discrimination, and are more vulnerable to losing their rights.

The Global Education Monitoring Team, the UN Girls’ Education Initiative and the Foreign and Commonwealth Development Office are committed to strengthening the arena of data collection, discussion, and analysis so that they most accurately reflect the situation of children on the ground, especially the most vulnerable children. This includes bringing in those actors who work directly on the ground to hear how they use global data and evidence and what they want from it. It also means bringing together different frameworks that are being developed to measure gender equality in and through education to inform investors in and champions of girls’ education and empowerment.

We welcome the ideas, viewpoints and perspectives of readers of this report who would like to join us in charting this way forward. Above all, the data and evidence in this report make clear that the most marginalized child, especially when she is a girl, needs concerted action from all of us.

English

English العربية

العربية Български

Български Hrvatski

Hrvatski Čeština

Čeština Dansk

Dansk Nederlands

Nederlands Suomi

Suomi Français

Français Deutsch

Deutsch Ελληνικά

Ελληνικά हिन्दी

हिन्दी Italiano

Italiano Română

Română Русский

Русский Español

Español Maltese

Maltese Zulu

Zulu አማርኛ

አማርኛ